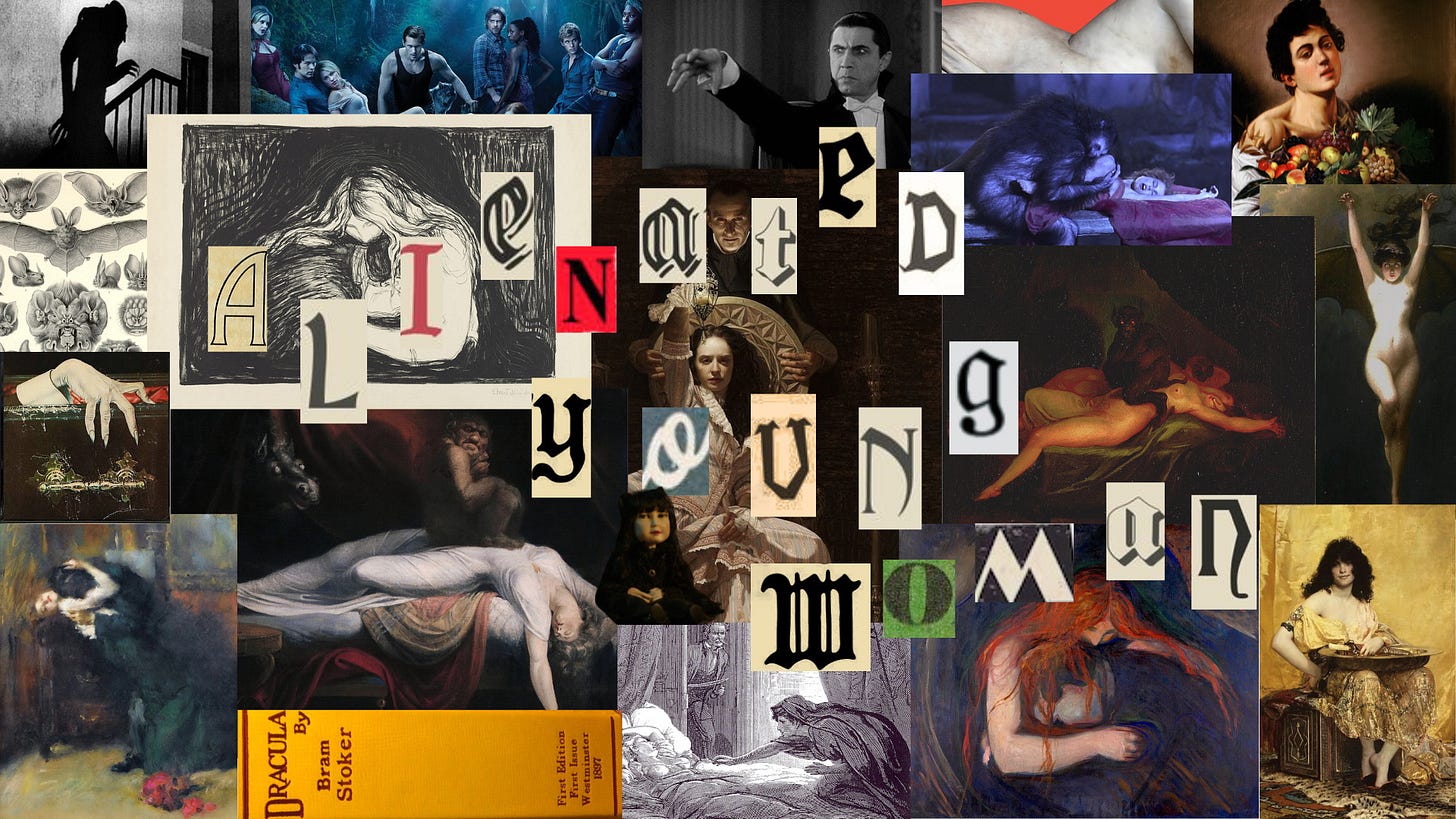

A Definitive Ranking of Vampire Media

An ode to the vampire in all its forms—Carmilla to Lestat and everyone in between

Thanks for reading Alienated Young Woman! Subscribe for free to receive biweekly book recommendations like this one in my newsletter, “What I’m Reading.”

Pro-tip: This post may be cut off via email, so try reading on your browser or via the Substack app.

In the two centuries since John William Polidori’s short story “The Vampyre” brought the folkloric creature into the English canon, we’ve been hooked on the vampire. It’s not surprising: there is something seductive about the creature who straddles the line between human and monster, a familiar body with unfamiliar power, transgressing social codes without inhibition.

In Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, vampire hunter Abraham van Helsing—a character who has come to define the genre in his own way—gives his readers a warning: Dracula, he says, will soon become “the father and furtherer of a new order of beings.”

He was right.

Dracula—and before then, J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s oft-overlooked 1872 novel Carmilla—cemented the vampire genre in history, but its staying power comes from a cycle of constant rebirth. Long after Stoker’s death, the vampire would be born again, and again, and again: with F.W. Murnau’s film Nosferatu in 1922, with Bela Lugosi’s iconic take on the character in 1931, in the mid-1970s with Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles, in the 1990s with Blade, in the 2000s with Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight saga and Charlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire Mysteries, in the 2010s with Jemaine Clement’s mockumentary What We Do in the Shadows, and with hundreds upon hundreds of others.

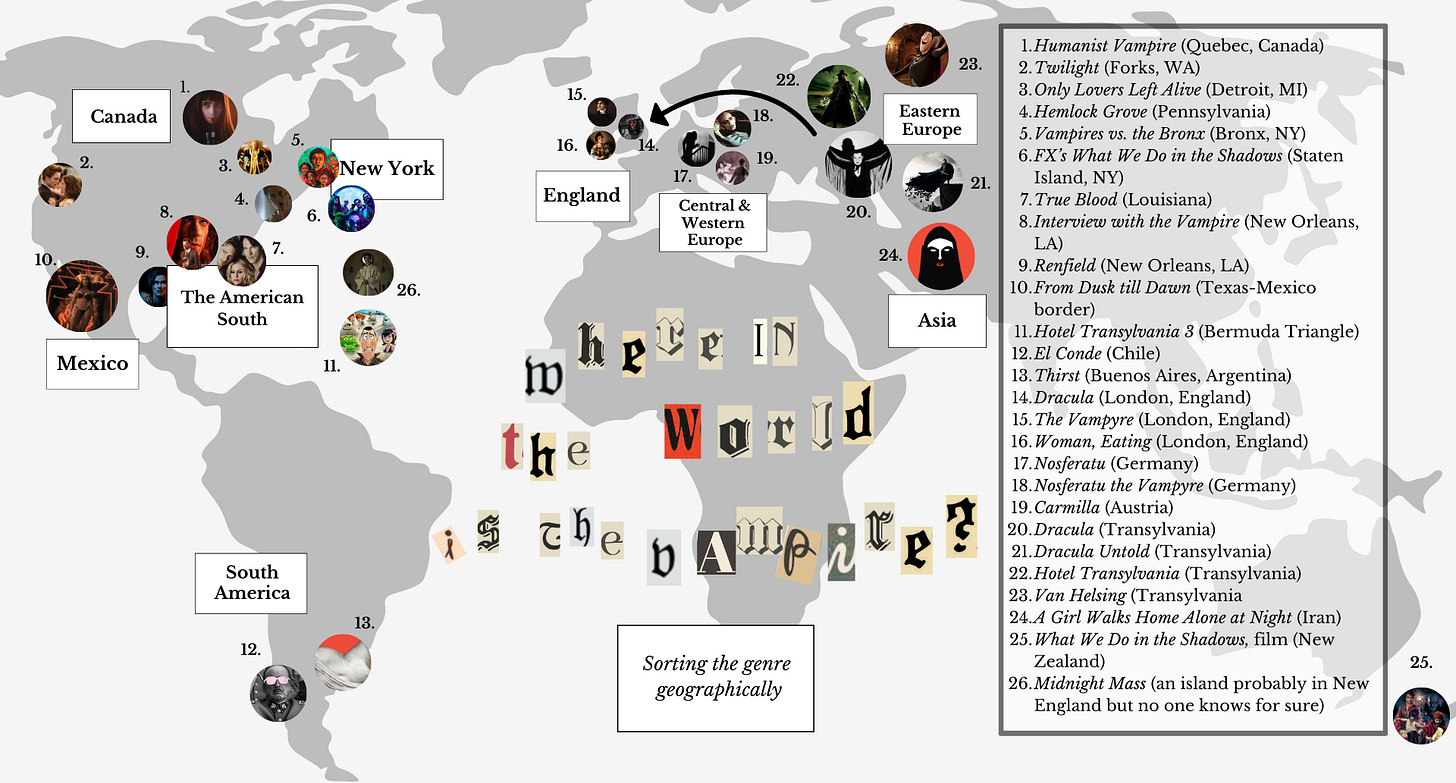

The vampire is that most versatile of monsters, on whom its creators have reflected any number of social fears. The vampire has been, in its past 200 years of life, a metaphor for queerness, greed, immigration, assimilation untamed sexual desire, gender fluidity, political change, and countless other taboos. It has been a villain, a victim, and everything in between. It has made its way from Transylvania, the cultural origin of the myth, to the farthest reaches of the world beyond, New Orleans to New Zealand. It has been a canvas canvas for bigoted fears and an outlet for marginalized fables.

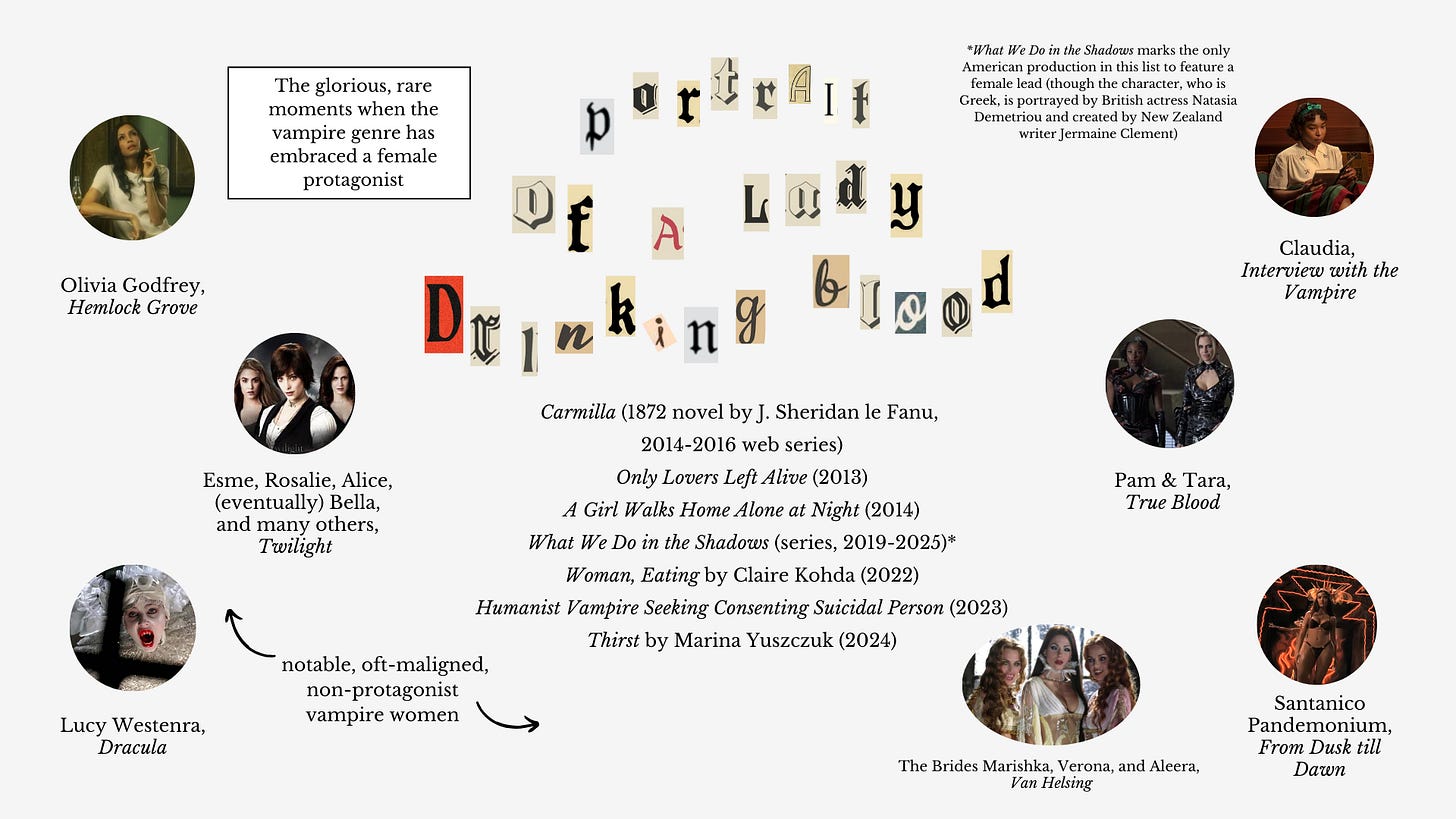

It’s a cycle fitting for vampirism, itself a rebirth into eternal life. Beyond its thematic changes, since the 19th century, the vampire’s physical presence itself has evolved from the leering Eastern European nobleman Polidori and Stoker imagined into any number of creatures more fitting for a newer era: an eternally-teenaged heartthrob, a Louisiana sheriff, a lonely queer college student, a high camp rockstar, an overprotective single dad, even, sometimes, a vampire-hunting vampire. On a glorious few occasions, the genre has even broken from the mold of being a metaphor for subversive identities and actually featured marginalized characters. All the while, its dedicated followers have only grown.

The vampire canon is infinite—or at least it seems so, an insurmountable subject to analyze and rank in its entirety. But there are unequivocal highlights—a lot of them.

Honorable Mention: Van Helsing (2004, dir. Stephen Sommers)

My dearest Van Helsing (2004). You are not a good film. Your central vampire is horrifically miscast. Your plot is confusing, and your dialogue is bad. But you opened with Count Dracula murdering Victor Frankenstein, his freelance employee, in order to gain primary custody of Frankenstein’s monster, whom he believes holds the key to perfecting vampire IVF. You closed with a surprise Bible tie-in. This is not to mention your actual central plot, which follows a young, sexy, Winter Soldier-esque Van Helsing (Hugh Jackman) in his quest to save werewolf kind. May all vampire media that comes after you be so bold.

The Top 25*

Actually 28—this is a living document

28. Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation (2018, dir. Genndy Tartakovsky)

In many ways, Adam Sandler’s Count “Drac” Dracula begins the animated Hotel Transylvania franchise as toxic of a father to his teenage vampire daughter as Interview with the Vampire’s infamous daughter-hater Lestat de Lioncourt. It’s a miraculous stroke of luck that Drac’s daughter, Mavis (Selena Gomez), is more forgiving.

Where Bram Stoker’s original Count Dracula may have been primarily concerned with creating a new race of monsters to aid him in taking over England, his animated counterpart—who bears a striking resemblance to Bela Lugosi, but lives by almost none of the classic vampire tropes2—is mostly concerned with carving out a safe haven in which to raise Mavis away from the dangers of bigoted humans. Enter the Count’s titular hotel, a safe haven for monsters of all forms hidden from human view, where, he believes, he and Mavis will live forever. So imagine his surprise when Mavis falls for a human, the very thing he’s dedicated his life to avoiding. Fundamentally, the Hotel Transylvania movies aren’t about vampires: they’re parables about fatherhood, grief, and occasionally, growth.

By Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation, Count Dracula has become what his audience would least expect: a changed man. He’s a doting grandfather to his half-human grandson, Dennis. He’s reconciled with his estranged father, Vlad. He’s even learning to adjust to humankind. Now, Dracula—who has spent the last two films enacting psychological torture to keep his daughter at home, who has spent centuries convinced vampires can only ever fall in love once in a lifetime, and who has spent zero movies experiencing personal growth—is suddenly discovering he may be deserving of love after all.

And if that love comes in the form of a human yacht captain voiced by Kathryn Hahn, who turns out to be the descendant of vampire hunter Abraham van Helsing, hellbent on the destruction of all vampires?1 Only a minor setback.

Ultimately, this is where the franchise’s third entry edges out its two predecessors: not in what it has to say about vampires, which is very little, but in what it does with its protagonist. For two consecutive films, we’ve seen Dracula as a father first, and a poor one at that, stunted by his own grief and transformed into a monster not by his bloodlust but by his constant fear of being alone. He gaslights. He manipulates. He kidnaps. He lies. But finally, in Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation, he gets a chance to have a life outside of parenting. For a vampire who has spent the better part of the last 150 years fearful of living without his daughter under his thumb, it’s a welcome change.

Yes, the vampirism in Hotel Transylvania is mostly a convenient backdrop with varying levels of relevance to the plot. No, the franchise is not anywhere close to the best vampire comedy (that title goes to FX’s What We Do in the Shadows), the best child-oriented vampire media (Sesame Street’s Count, obviously), nor the originator of the best Dracula-adjacent teenage girl (Monster High’s Draculaura). But what the films are—and especially what Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation becomes—is something special enough on its own.

27. Seasons four and five of HBO’s True Blood (2011-2012)

In the words of probable True Blood watcher Taylor Swift, “Stop! You’re losing me.”

The first season of HBO’s True Blood accomplished something magical. The second and third never quite recaptured that magic, but still made for excellent television. Following the misadventures of protagonist Sookie Stackhouse—a half-human, half-fairy, possibly psychic waitress—in the years after the development of a synthetic blood substitute allows vampires (and eventually, all sorts of supernatural beings) to emerge from the shadows, the early seasons of True Blood balanced camp with allegorical storytelling in a way that brought the genre to life in vivid color, embracing beautifully ridiculous without losing sight of quality storytelling. They were a love letter to the Southern Gothic that allowed the series’ ensemble cast to work in perfect harmony, even in the most outlandish of circumstances.

In seasons four and five, however, the magic faded. The focus of the storyline rapidly shifted from Sookie’s romantic entanglements against the backdrop of vampire-human political tensions to something broader, and much harder to follow. Sookie’s slow-burn vampire love interest Bill Compton (Stephen Moyer) may have entered the series seeming like the first and only vampire in the fictional town of Bon Temps, Louisiana, but somehow, by Season 4, the isolated community is actually home to an entire monster ecosystem with intricate politics of its own.

In a plot line that completely engulfs Season 5, we discover more than we’d ever wanted to know about the inner workings of the vampire government (which, as it turns out, is mostly sex-and-vibes-based and run by Christopher Meloni with the help of the mythical Lilith). Before then, we meet werewolves (a worthy addition to the True Blood universe) and their more confusing counterparts, werepanthers (an unworthy addition). Also, witches exist, they live in Bon Temps, and they’re preparing to enact a Jonestown sequel (but Fiona Shaw is there, guest-starring as witch cult leader Marnie, so all hope is not entirely lost). With a bloated cast, an ever-growing number of subplots, and the absence of the anchor that the Sookie/Bill romance provided in the series’ first three seasons, everything just became more difficult to follow from there.

But the worst crime of these middle two seasons is what they did to seminal hot vampire Eric Northman (Alexander Skarsgård),2 who is ripped from his central purpose (wearing little tank tops) and forced into a Saw trap of increasingly nonsensical scenarios. He experiences amnesia that briefly makes him pure of heart. He abandons bisexuality in favor of a Wuthering Heights-esque romance with a previously unrevealed adopted sister. He leaves vampire law enforcement. He becomes a landlord.

Still, somehow, the downward spiral doesn’t end there. The bafflingly convoluted fifth season was simply a warmup, the fourth an exercise in camp that went too far and failed to reel itself in. True Blood, after all, had seven seasons, and creator Alan Ball departed ahead of the sixth. For the vampires of Bon Temps, things could—and would—get worse.

26. Dracula, the miniseries (BBC, 2020)

Dracula—that is, Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat’s 2020 BBC miniseries adaptation of Dracula—is a tragedy, but not in the way you’d expect. It’s not the tragedy it poses itself to be: a tragic love story about a man alone in his immortality, blending the camp and cleverness of True Blood with the melancholy of Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre. No, BBC’s Dracula is a tragedy because of everything it isn’t. It’s a tragedy because, for all intents and purposes, it found the perfect Dracula in Danish character actor Claes Bang, and plopped him into a Dracula that was anything but.

Dracula begins more or less faithful to its source material, the first of its three hour-long episodes opening with a frightened Jonathan Harker entering the castle of the aging vampire. It doesn’t stay that way for long. Still, that the adaptation proceeds to fundamentally alter the story in order to suit a different sensibility is not the issue. Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula gave the character a tragic origin story, one in which his vampirism felt somehow justified. Hotel Transylvania imagined Dracula as a doting father, and Jonathan Harker as his goofy human son-in-law. In a story retold as often as Dracula, change is not a negative factor on its own.

But there is something soulless in what BBC’s Dracula does with its titular character. It’s no fault of Bang himself; in Dracula, the actor—whose work from Bad Sisters to The Northman proves chameleonic every time—is sexy and magnetic with a kind of performed confidence that only further cements his otherness. But he is failed at every turn by the parameters of the story he’s been tasked to tell. Most notably, this Dracula’s obsession is not with Mina Harker, as it’s often portrayed, but with the (now female) vampire hunter Van Helsing (who is now two distantly related women, both played by Dolly Wells). There may be a way to make that change compelling, but Gatiss and Moffat did not find it. Instead, their changes to the text feel like the decisions of writers afraid their audiences were not quite intelligent enough for the original story.

Structurally, the issues with BBC’s Dracula are rife. The first episode makes for a confusing pastiche of the book that devolves into a nunsploitation slasher. The second drags out the novel’s long-since obsessed-over travel sequence—in which Dracula travels from Transylvania to London on the cargo ship the Demeter, picking off the crew one by one along the way—a sort of watered-down Last Voyage of the Demeter three years before the film itself premiered. By the third and final episode, it’s inexplicably 2020, the titular Count is less than halfway through his predetermined story, and things go from convoluted to impossible. Bastardizing Dracula’s source material may have been a forgivable sin, but bastardizing it in favor of a plot somehow less conducive to the miniseries medium—one that limits Bang time and time again, flattening him into a one-dimensional Frankenstein’s monster of his Hot Vampire predecessors—is beyond absolution.

25. “The Vampyre” by John William Polidori (1819)

It was 1817, and Frankenstein was germinating in Mary Shelley’s mind during an eventful vacation to the Swiss Alps where she, husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron had challenged each other to write the most terrifying short stories they could think of. Across the hall, a lesser-known writer had taken up the same challenge: John William Polidori, a sometime writer and Byron’s personal physician. As Shelley laid the groundwork for her foundational horror novel, Polidori was drawing on folklore to produce “The Vampyre,” a nine-page story about a young man seduced by an enigmatic aristocrat, only to discover his magnetic appeal is concealing something beyond comprehension. It was the vampire’s creepy, gory, ornate induction into the English literary canon.

It was no Frankenstein. Its nine pages were rarely as thrilling as what would come next. But it was the dawn of a genre; with its publication, the vampire—and literary horror—would never be the same.

24. Carmilla, the series (YouTube, 2014-2016)

Often, when we discuss innovation in the vampire canon, we mean it in the context of genre or demographic. Ana Lily Amirpour’s Western-inspired A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night featured a female, Persian, skateboarding vampire. Rolin Jones reimagined Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire with a Black man—rather than a slaveowner—as the protagonist. Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi made an inspired choice to film What We Do in the Shadows as a mockumentary.

But Carmilla, the cult-classic YouTube series from creator Jordan Hall, innovates on multiple fronts. On one hand, it follows in the footsteps of Twilight and the CW’s The Vampire Diaries by placing its vampires in the context of a teen drama, setting its adaptation of the 1872 novel in the present day, and exchanging the book’s isolated castle setting for a small liberal arts college, where protagonist Laura and the titular vampire are unlikely roommates. But in an even bigger turn, Carmilla also innovates with its form: the story is told in 121 mini-episodes, each a single scene less than five minutes long and shot almost entirely from one stationary location—the desk in Laura’s dorm room—as if the entire series itself is a YouTuber’s vlog. Such a format makes the series just as much of a time capsule for the American 2010s as the original is for the Western European 1870s. In that sense, it’s one of the most effective adaptations on this list.

Another force behind the series’ effectiveness: Carmilla is unafraid to eschew the original text for a modern sensibility, becoming all the more distinct each time. It brings the vampire into the teen detective framework, but—unlike its aforementioned predecessors—it does so without attempting something so heavy it becomes soapy. Instead, the single-scene shorts adopt a tone more in line with a cross between Veronica Mars and a grown-up Victorious. And, in a genre where strikingly few adaptations of the classics have embraced the unmistakable queer themes in their source material, Carmilla leans in.3 If Carmilla is first and foremost a vampire mystery, then it’s secondly a drama about 19-year-old lesbian friend groups. That the series achieved such a cult following with this premise is hardly a surprise.

The very best adaptations are just as successful as standalone works of art, and, in more ways than one, Carmilla certainly stands alone.

23. Vampires vs. the Bronx (2020, dir. Oz Rodriguez)

What if Stranger Things had swapped the Duffer brothers for the culturally nostalgic, occasionally corny diasporic Latino earnestness of Shea Serrano or One Day at a Time? What if the series had quit while it was ahead?

The result might have been something like Vampires vs. the Bronx, director Oz Rodriguez’s debut feature about three Bronx preteens trying to save their rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, only to find their opponents are far more insidious than they seemed. Chock full of homages to vampire history, unafraid to be cheesy, and always ready to maximize the fun, Vampires vs. the Bronx is an endlessly fun, strikingly earnest take on the vampire action movie, one made all the better for Rodriguez’s love of the genre.

22. El Conde (2023, dir. Pablo Larraín)4

One element of the iconic vampire Count that many later entries in the canon have chosen to gloss over or leave behind entirely: his greed. If there is a class critique to be found in Dracula, it’s in the vampire’s precarious status, a fading aristocrat in a world where the title is losing its meaning, using his immense fortune and even greater power to exert his will where he can, subjugating as many as possible along the way. He has endless resources to move through the world, and—left unchecked— endless world to conquer.

In that sense, perhaps there’s no better vampire than a dictator. That Augusto Pinochet, who spent two decades in power as the brutal leader of Chile, is the central vampire in Pablo Larraín’s El Conde feels only natural. Here is a man whose brutal regime killed thousands of his own constituents, imprisoning, torturing, and disappearing thousands more, all while his own fortunes grew in secret. Does sating his appetite by cutting out a few human hearts really make his evil any worse? If the first Count Dracula had not been stopped, could even he imagine such carnage?

In Larraín’s pitch-black horror comedy, Pinochet’s final days play out something like Logan Roy’s in Succession, had Logan consumed human flesh. After living for 250 years, the bloodthirsty dictator is aged, dawdling, and ready to die. His family—philandering wife Lucía and their five irresponsible, middle-aged children—are supportive of this goal, so long as they get the chance to exorcise every last drop of their father’s hidden fortune before he’s gone. “Beyond the killing,” one family member tells us, “his life’s work was to turn us into heroes of greed.”

Larraín’s whip-smart script hardly shies away from the real-life brutality of its subject. Instead, with a razor-sharp satirical eye and pitch-perfect (and occasionally, almost Trumpian) performances from Jaime Vadell as Pinochet and narrator Stella Gonet, El Conde is an unflinching lampoon of all-too-real monstrosity.

21. What We Do in the Shadows, the film (2014, dir. Jemaine Clement & Taika Waititi)

We cannot possibly talk anymore about moving the genre forward without talking about What We Do in the Shadows. Filmed on a shoestring budget in New Zealand as the brainchild of longtime collaborators Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement, the mostly improvised mockumentary was a turning point for the vampire canon. Two decades after Mel Brooks deftly parodied the vampire in Dracula: Dead and Loving It, Clement and Waititi infused their own vampire parody with a 2010s mockumentary sensibility, finding an irreverent, strikingly earnest brand of humor and carving out a niche in the process. Once again, the vampire had become something new.

What We Do in the Shadows is scrappier than the series that followed, and at times, more ambitious for time parameters. Ultimately, that often makes for a less cohesive end product, but one that built the scaffolding for much greater vampires to come.

20. From Dusk till Dawn (1996, dir. Robert Rodriguez)

In the 28 years since Robert Rodriguez’s cult classic hit theaters, the genre has grown gradually fonder of the Latino vampire. Or rather, the genre has grown fonder of the South American vampire, in the particular form of fallen nobility—like those in Pablo Larraín’s El Conde and Marina Yuszczuk’s Thirst—clinging to their long-gone Europeanness as their adopted country crumbles and rebuilds around them. But From Dusk till Dawn is a different kind of Latino vampire movie: one about border vampires. As we learn in a final shot that clinches the film’s sometimes shaky premise, that is a different, more visceral creature.

Written by and co-starring Quentin Tarantino, From Dusk till Dawn is set just over the boundary from Texas to Mexico, where bank robber Seth Gecko (George Clooney) and his psychopath brother Richie (Tarantino) have taken a grieving pastor and his two teenage children hostage in an attempt to smuggle themselves out of the United States. But when the group of misfits makes a pitstop at an enigmatic biker bar, they soon learn nothing is what it seems on the other side of the border, and their attempt to run from the law becomes a mad dash to survive the night.

Here are vampires—the employees of this fantastical bar—whose material existence on the border has negated the kind of aristocratic grandeur we’ve come to expect of the monster, and whose victims—serial killer Americans—are no less monstrous. An entire world has grown up around them, destroying theirs in the process, until they had nothing left but their supernatural gift. Can you blame them for having a bit of fun using it?

From Dusk till Dawn is not always as inventive as it hopes to be. Or rather, the more glaring of its issues sometimes detract from just how inventive it is. The film is unsparingly, irrationally brutal to its few women characters (with Tarantino behind the script, who’s surprised?). But it pioneered the vampire western two decades before A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night laid claim to the genre. It didn’t always succeed in its critiques. But it made a ghost town of the border and inside of it, imagined a new kind of vampire.

19. Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person (2023, dir. Ariane Louis-Seize)

The 2020s seem to have ushered in a new preoccupation for the vampire genre. Alongside the demons, succubi, and social outcasts—all of whom remain bountiful—a less insidious vampire has emerged: a young woman who has inherited the gift genetically and does what she can to avoid acting on the urge, all while learning to live away from her vampire parents for the first time. Call Charli: the apple’s rotten right to the core. It’s the vampire’s feminist bildungsroman.

What sparked this trend? Was it a long-overdue nod to the isolated girlhood of Carmilla, the elder sister of all woman vampires to follow? An offshoot from the dawn of post-COVID magical realism? A response to the codependence and arrested development we saw in the genre’s other foremother, Hotel Transylvania’s Mavis Dracula?

In any case, the emergent sub-genre found its way into French Canadian cinema last year with Ariane Louis-Seize’s Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person, an endearing coming-of-age comedy that follows a teenage vampire working to overcome her aversion to murder and the depressed human teen who volunteers himself as her first victim.

Nascent as the sub-genre may be, Humanist Vampire—borrowing notes from Woman Eating with a hint of The End of the F***ing World—doesn’t necessarily feel as innovative as it’s been marketed to be. But it also doesn’t have to. Enthralling, disarmingly charming, and unexpectedly sentimental, it’s a highlight of the growing movement and a refreshing vampire tale all on its own.

18. Dracula, the film (1931, dir. Tod Browning)

For nearly two decades after Bram Stoker’s death in 1912, his widow, Florence Balcombe, kept the film rights to his iconic novel close to her chest. Her legacy in history is cemented by her decision to make an example of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu when it borrowed heavily from her husband’s creation, coming down so hard on the filmmakers that nearly every copy of the film was destroyed.

Bela Lugosi changed her mind.

After embodying the character in a stage production, Lugosi—already in love with Stoker’s vampire—made a personal appeal to Balcombe, convincing her to sell the rights to Universal and giving way to Tod Browning’s 1931 film. It was a smart move; Lugosi’s portrayal, driven by his reverence for Stoker’s creation, shaped the public image of Dracula more profoundly than anyone but the author himself, and had a greater impact than any portrayal since. Lugosi’s looming aristocratic monster is still the one we picture when we think of Dracula. Hints of him linger in nearly every vampire since.

But Browning’s film is not its central character. To fit the brand new monster movie identity—or perhaps, just to make room for Lugosi’s massive performance—the film shrinks itself around him. The star carries Dracula’s grandiosity, so, for better or for worse, the rest of the film tends to feel empty without him. Lugosi may have defined Dracula, but he didn’t get the adaptation he deserved.

17. Midnight Mass (Netflix, 2021)

Though it contains many of creator Mike Flanagan’s hallmarks (and his favorite recurring cast members), Midnight Mass still feels like something new for the Netflix horror giant. For one, the miniseries is a departure from his preferred source material; unlike past megahits The Haunting of Hill House, The Haunting of Bly Manor, and The Fall of the House of Usher—all of which were inspired by works of classic horror literature5—Midnight Mass is an original story. Inspired in part by Flanagan’s real-life upbringing in the Catholic Church, Midnight Mass is the story of a remote island where the arrival of a new priest (Hamish Linklater in a career-best performance) heralds a slew of supernatural occurrences, both miraculous and existentially threatening.

Setting itself apart even further from Flanagan’s past work, the horror in Midnight Mass is slow-moving. Where the supernatural phenomena of Hill House et al make themselves known by the end of the pilot, Flanagan spends the first half of Midnight Mass’ seven episodes letting his monsters lurk in the shadows.

But Midnight Mass is not just a departure from Flanagan’s own body of work: his most personal series yet also approaches vampirism from practically the inverse of most other vampire media. That is, rather than inspire condemnation as the so-called spawn of Satan, the strange creatures of Midnight Mass are hailed as miracle workers by a town already on a slow descent into religious fanaticism, its residents so steadfast in their faith that they become an entire community of would-be R.M. Renfields. On Flanagan’s island, the Catholic Church protects the monsters—it always has.

16. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014, dir. Ana Lily Amirpour)6

As discussed, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night may not be the first-ever vampier Western. That fact does not actually come anywhere close to negating the film’s fierce originality. Instead, the first Iranian vampire western is unpredictable, creeping, sexy, and poignant, a tale about leaving your home before it crumbles around you. It somehow manages both the highly-curated aesthetic storytelling of Larraín in El Conde or Rolin Jones in AMC’s Interview with the Vampire and the urgent scrappiness Jordan Hall brought to Carmilla or Clement and Waititi to What We Do in the Shadows.

Anyway, complete originality is not a prerequisite of good vampire media—this list would not be so rife with Dracula adaptations if it were. But Amirpour’s creation is so gleefully unlike the canon that came before her that this, too, becomes part of the story. A century after the passive, brutalized Brides of Dracula made their debut, Amirpour’s vampire lives under the same male gaze but trades in rage. As mysterious and omnipresent as the vampires who loomed in the shadows before her, the female, Persian, skateboarding, gang-fighting creature at the center of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is at times presented as the archetypal vampire—other times, she explodes that archetype altogether.

15. Only Lovers Left Alive (2013, dir. Jim Jarmusch)

From Carmilla forward, the vampire genre has been preoccupied with loneliness. As audience members, we often meet our vampires centuries into their mortality, wandering the Earth in search of an end to their isolation—their next kill, a coven of fellow vampires, a companion they won’t outlive. But in Jim Jarmusch’s foray into vampirism, loneliness takes a different form. The vampires of Only Lovers Left Alive (a perfectly cast Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton) begin their journeys having already found their mortal companions (each other), and even an entire ecosystem of fellow vampires. It’s not enough to stifle their oppressive loneliness. Immortality itself—even immortal companionship—is inherently isolating. Against the backdrop of folkloric horror, Only Lovers Left Alive is played like a monstrous Scenes from a Marriage; the mundanity of hitting career lulls and having conflicts with in-laws is no less relevant to the ebb and flow of vampire life than the need to discreetly consume human blood. In a world where “till death do us part” truly means never parting, is anything enough to keep a centuries-old love alive?

14. Thirst by Marina Yuszczuk, translated by Heather Cleary (Dutton, 2024)

Quiet as it’s been kept historically, when it comes to the vampire novel, queerness—and specifically, female queerness—may be the most inherent of its themes. The vampire novel is, after all, a meditation on social taboo, irrepressible desire, and a lifetime of otherness. It was J. Sheridan le Fanu who brought the vampire to the form in 1872 with Carmilla, and he did so with what can only be read as a tragic romance between two young women, isolated by circumstance and othered by desires they can’t control. In that sense, Thirst, by Argentine horror darling Marina Yuszczuk, returns the vampire genre to its roots.

In Thirst, a nameless vampire wanders through Europe for decades, ostracized by the Church, before settling in the shadows of Buenos Aires in the 19th century. Silent in the dark as the city forms around her, the vampire slowly disappears into her monstrous grief. Then, halfway through the novel, she disappears from the reader as well; Yuszczuk shifts the story’s perspective to an equally lonely human woman, an anthropologist grappling with her mother’s terminal illness and unknowingly wandering the grounds of the very cemetery where the vampire lies in wait. Pulling Le Fanu’s meditations on otherness and sexual taboo into a modern understanding of queer desire, Yuszczuk crafts an eon-spanning tragic romance that somehow feels just as timeless as its predecessor—if not even more so.

13. Twilight, the film (2008, dir. Catherine Hardwicke)

The vampire genre, in its modern iteration at least, is nothing without the vampire teen drama. It’s a form that embraces the canon in all its melodrama, campy and sexy and, most compelling of all, blending the anxiety of coming of age with the existential horror of eternal life.

The vampire teen drama is nothing without Twilight. From its initial release in 2005, the original novel series from Stephanie Meyer was impactful enough on its own. But it was the film series—beginning with Catherine Hardwicke’s megahit in 2008—that cemented Twilight’s status as a cultural touchpoint. It was, and remains, the seminal teen vampire drama.

In the film so powerful it captured the unwavering attention of our most Dracula-esque president, Hardwicke blends her one-of-a-kind aesthetic (and sonic) vision with the best of Meyer’s storytelling, bringing a subversive artfulness to a long-maligned canon. But it was Kristen Stewart, Robert Pattinson, and the impeccable ensemble cast’s no-holds-barred, full-throttle performances that gave the film its beating heart, bringing Twilight so far beyond what the books could accomplish. They leaned wholeheartedly into the ridiculousness—and it worked.

12. What We Do in the Shadows, the series (FX, 2019-2025)

Most of the entries on this list are adapted—faithfully or loosely—from a few vampire classics (mostly Dracula, sometimes the works of Anne Rice or Charlaine Harris, and occasionally, even Carmilla). In this regard, FX’s What We Do in the Shadows holds a curious status, the reimagining of a relatively new piece of vampire media (the 2014 film) that builds on its source material more effectively than most—if not all—of the other adaptations on this list.

Though it shares the same general premise as the film, the series, also developed by Jemaine Clement, introduces us to a new set of vampire roommates: former Ottoman ruler Nandor (Kayvan Novak), nymphomaniac Georgian-era English gentleman Laszlo (Matt Berry), Greek Romani businesswoman Nadja (Natasia Demetriou), self-described “energy vampire” Colin (Mark Proksch), and their long-suffering human familiar, Guillermo (Harvey Guillén). Rather than New Zealand, the roommates live on Staten Island, having once hoped to claim the Americas for vampire-kind and now generally happy living a mundane existence as New Yorkers. It’s one of many welcome updates.

As Laszlo and Nadja, Berry and Demetriou give career (and genre)-defining performances that blend endearing spoofs of classic monster media with Clement’s off-kilter humor. But it’s Guillén who truly steals the show as Guillermo, the overworked and underloved vampire-enthusiast familiar with a whip-smart humor that only makes his earnest moments all the more powerful.

If the leads of FX’s What We Do in the Shadows were not already better constructed than the film’s, they would still benefit tenfold from the series format. The transition from mockumentary to mockumentary-sitcom allows each character all the more room to develop, and the series seems to find new ways to tap into its main cast’s comedic strengths with each season. (And, to be clear: Novak, Berry, Demetriou, and Proksch do make for better vampires than their predecessors). Like vampires themselves, What We Do in the Shadows has only gotten stronger with age.

11. Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922, dir. F.W. Murnau)

If there are any points to be given out for ingenuity or cultural influence, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu would earn all of them. Shot in 1921, when the vampire was still a developing genre and film itself was a nascent medium, Murnau’s German expressionist silent movie brought forth an ancient terror. Loosely adapting Dracula—albeit, without permission—Nosferatu saw German actor Max Schreck transform completely into his version of the monster, a primordial, demonic creature who crept across the screen until he’d burrowed into the conscience of his victims—and his audience. That a legal dispute with Stoker’s estate led to the destruction of most original copies of the film proved only a hiccup in the long arc of history; in the sacred canon of vampire classics from which the rest of the genre pulls its inspiration, Nosferatu is forever.

10. Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda (HarperVia, 2022)

If Humanist Vampire felt at all unoriginal, it was only because Claire Kohda’s Woman, Eating already exists. Set in London, the one-time home of the original literary vampires, it’s Kohda’s novel that feels somehow never before seen. Or rather, the novel brings together a centuries-old character—the young woman vampire—and a centuries-old genre—the künstlerroman (an artist’s coming of age)—and manages, in a work of genius, to emerge with something fresh and new. In this case, it’s the vampire Lydia, a mostly ordinary 23-year-old biracial artist newly living on her own after moving her 400-year-old mother into assisted living. Socially awkward, burdened by generational trauma, and shaky in her independence, Lydia is nearly the prototypical alienated young woman—except, of course, that she’s also staving off an insatiable bloodlust. In that regard, Kohda’s meditative, poignant, contemporary novel is singular.

9. Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979, dir. Werner Herzog)

What if Count Dracula were Big Edie? Rather, what if his formidability fell away, leaving behind a lonely, fading aristocrat, longing only to return to his days in the sun? Werner Herzog is unafraid to ask those questions. Nosferatu the Vampyre—part remake of the 1922 film, part adaptation of the original text—sees in the iconic vampire a depressed, aging monster, as desperate to be loved as he is to find his next victim. As Dracula, Klaus Kinski is unabashed in his theatricality, combining the flamboyance of Max Schreck's original vampire with an undercurrent of something heavier. It’s Dracula at his least gory, and, occasionally, his campiest.

8. Hungerstone by Kat Dunn (Zando, 2025)

How is it that we as a culture are so starved for (good) Carmilla adaptations? Of the roughly 35 pieces of vampire media discussed in this piece, 13 are reimaginings of Dracula. Only one other is a direct adaptation of Carmilla, the novel that Dracula would not exist without.7 For all the vampire’s importance as a reflection of societal taboo, it has taken us ages to move beyond the genre’s white, (sometimes) heterosexual male figurehead to embrace its sapphic progenitor.

Finally, a century and a half after Le Fanu’s original novel, English horror author Kat Dunn seeks to rectify that gap. In Hungerstone, imagines the same vampire in a new setting: ten years later, in an England transformed by the Industrial Revolution. Critically, the vampire also has a new object of her desire: not the naive teenage Laura of the Styrian wilderness, but the older, more jaded Lenore, an aristocratic wife. Friendless, orphaned, and turning 30, Lenore is perhaps even more isolated than Le Fanu’s Laura. She fears her own darkness, and struggles to grant her husband Henry’s only wish—an heir—when she begins to realize he may not be worth such a legacy. She’s butting up against the confines of married, aristocratic propriety—and facing the punishment for it—long before a seductive stranger arrives on her doorstep.

So when Carmilla does arrive, and her presence yields strange happenings at Hungerstone, Lenore’s dilapidated country estate, uncovering dark truths about her past and Henry’s present, perhaps her monstrousness isn’t so frightening. Perhaps it’s exactly what Lenore needs to satiate her hunger.

Dunn’s take on Carmilla is just as seductive—and just as haunting—as the original. But her bounds are loosened by another century and a half of evolution and literature, allowing her room to explore parts of the story Le Fanu left uncharted. In that empty space, she weaves in elements of Le Fanu’s contemporaries in Victorian sensation fiction, like Gilman, the Brontës, Wilkie Collins, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon. But there is also a fiercely original strain infecting Hungerstone: Dunn imagines for her protagonist what Le Fanu could not for his, a liberation he had to trade in for fear.

If the original vampire novels were written in fear of otherhood, Hungerstone dives headfirst into the once-unspoken taboo. Carmilla’s taboo passion, the ghost that lingered over Le Fanu’s novel, is no longer taken as monstrousness, but by the same token, the story could not exist without it. Dunn gives her the space to exist as a fundamentally, unquestionably sapphic monster, just as motivated by desire as the original, but no longer a boogeyman. Finally, she’s free to be queer.

7. The first three seasons of HBO’s True Blood (2008-2010)

Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that the Southern Gothic favors the vampire. It is a canon shaped by the ghosts of the past, one where structural and societal change haunts the narrative alongside spirits, human monsters alongside the supernatural. Decay looms heavy—as do the sins that preceded it. Who better than a vampire to watch in resigned horror as the world changes around them?

None of this comes close to capturing just how much True Blood had going on. Adapted from Charlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire Mysteries novel series, the HBO drama was never afraid of being too much. Beautiful, horny vampires (still a rarity when the series premiered) mingled with humans, then with werewolves, fairies, witches, shapeshifters, and a few creatures of Harris’ own creation. There was no plot line too out of left field, no topic too big to broach.

But the series wasn’t just unafraid of camp—it was unafraid of pushing boundaries. When True Blood was at its best, Ball saw vampire-as-taboo, the very trope for which the monster was created, and brought it to life as few others seemed to have the guts to do. Just over a decade after the AIDS crisis waned, Ball and Harris did what the literary vampire was always intended to do, and used it to reimagine a real-life moral panic. In True Blood—at least, in the early seasons of True Blood—vampirism was a liberating thing.

For one 12-episode season, Ball had struck gold. It was campy, gory, sexy, and always, above all, a blast, with sharp humor, a creeping horror, and a nuanced grip on the sometimes suffocating experience of the American South. For two subsequent seasons, Ball had struck something that at least felt like it. Ball saw the potential in the show’s supporting cast—from Nelsan Ellis as flamboyant medium Lafayette to Rutina Wesley and Kristin Bauer van Straten as formative bisexual anti-heroes Tara and Pam, to Alexander Skarsgård’s Viking vampire sheriff Eric Northman—and allowed them space to grow into fan favorites. If only Ball had quit while he was ahead.

6. Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

It may open with an entirely original prologue, but Francis Ford Coppola’s take on the classic is called “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” for a reason. Sprawling, unabashed in its decadence, and unafraid to be both dread-filled and horny, it is perhaps the most truthful adaptation of Stoker’s original text to date. At the very least, it’s the one that best understands what’s at the core of Stoker’s novel: Victorian anxieties about immigration, otherness, and unrestrained sexuality. If Dracula was, above all, a novel about the dread of an England transformed, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a film that realizes that vision, transforming the monster from its prior Lugosian confines along the way.

As Dracula, Gary Oldman is truly transformative, disarming to the point of near-camp in the film’s first act, with a terrifying intensity in the second. He becomes, at times, the anti-Lugosi, reshaping the monster into someone suave, sexy, and almost perfectly human. His is a different kind of unflinching stare, one that conceals the actual terror underneath. But it’s Winona Ryder’s Mina Harker—in all her innocence, all her supreme heroism—who captures the film’s heart. (Say what you will about Keanu Reeves and his steadfast commitment to giving his Jonathan Harker an English accent he never quite mastered, but his earnestness and naivete in the role make him stand out in the character’s long lineage.) Perhaps this was the adaptation a lover like Lugosi deserved.

5. Interview With the Vampire, the series (2022-present, AMC)

The vampire television series is nothing new. Adaptations of Anne Rice’s novel series The Vampire Chronicles are nothing new. So, how does AMC’s Interview with the Vampire manage to feel so pervasively, consistently new?

The answer: In the true spirit of the vampire, the series is unafraid of transformation. The show’s premise itself is a reinvention of Rice’s source material: in creator Rolin Jones’ version of Rice’s world, titular vampire Louis de Pointe du Lac is not a white slaveowner in antebellum New Orleans when he meets his eternal vampire companion, but a wealthy Black man at the turn of the century. His interviewer is not, as in Rice’s novel, a scrappy 20-year-old reporter itching for his big break, but the same man 50 years later, worn down by time and trying to piece together his long-ago discovery of monsters. Both men are working from unreliable memories.

Perhaps the biggest shift of all: in Jones’ version, Interview with the Vampire is no longer a metaphor for queer desire, buried deep within the intricacies of the vampire bond, but an explicit celebration.

As Louis and his immortal lover Lestat de Lioncourt, Jacob Anderson and Sam Reid possess a power no other adaptation has so much as approached—they bring the characters to life perhaps more vividly than even Rice herself. But perhaps, at the core, this is what keeps Interview with the Vampire so fresh: it is perpetually, fearlessly building on the best of Rice’s work.

4. Nosferatu (2024, dir. Robert Eggers)

In the era of the Hot Lonely Vampire, Nosferatu returns to the roots—not the artistic, but the folkloric, the vampire at its most monstrous. Nosferatu’s Count Orlok, not unlike his two film predecessors, is almost unbearable to look at head-on, a terrifying mound of rotting flesh that looms over his victims long after they’ve left his presence—death embodied. But, true to the monster’s origins, he’s no less pervasively sexual. The nosferatu in Nosferatu is not just the manifestation of death, but of desires otherwise unspeakable in the puritanical confines to which the vampire was born.

Few actors in the vampire canon seem to have approached their roles with such a thorough, innate understanding of the monster as Nosferatu’s leads. Genre veteran Bill Skarsgård achieves the seemingly impossible as Orlok, blending traces of Stoker’s Dracula with a visceral, lingering monstrosity the author couldn’t have put to page. Lily-Rose Depp, meanwhile, is haunting as Ellen Hutter, the film’s Mina Harker-inspired heroine, commanding the screen not just as a woman confronting long-buried desires, but as a woman whose suffering—even as she screams for recognition—goes unheard.

But it’s Eggers—at peak form in his fourth historical epic—whose vision makes Nosferatu feel so unlike any other vampire story put to screen. In Nosferatu, Eggers employs the historical precision that made him a titan of horror so deftly that it makes even the darkest corners of the vampire’s world feel completely immersive. It’s the vampire at his bleakest, his realest, and his best in a long, long time.

3. Sinners (2025, dir. Ryan Coogler)

Let me stop you: yes, there was a brief moment when I considered this was recency bias, and that reworking my entire ranking to put this film at #3—making it the highest-ranked film on this list—immediately after leaving the AMC Lincoln Square IMAX Easter Sunday screening might be an overreaction. But Sinners may be impossible to overrate.

Set over a harrowing 24 hours, Ryan Coogler’s vampire saga begins and ends in a rich, haunting vision of the Deep South: Clarksdale, Mississippi, 1932. There, twins Smoke and Stack Moore (both Michael B. Jordan, in two career bests) have returned home after seven years making a name—and a fortune—for themselves in the mobs of Chicago, eager to open a juke joint for their close-knit Black sharecropper community. To do so, they’ll need help—from Annie, a gifted mystic and Smoke’s estranged lover (Wunmi Mosaku), aging Blues legend Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo), seductive singer Pearline (Jayme Lawson8), crafty Chinese-American shopkeepers Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo (Yao9), and most importantly, Sammie, the twins’ kid cousin with a prodigious gift for the Blues guitar.

Sammie’s music carries so much power that it’s said to weaken the bounds between the living and the dead, unearthing ancestors, but perhaps—as his pastor father insists—inviting the Devil in with them. It may also be the key to Smoke and Stack’s success at Club Juke and Sammie’s escape from his father’s iron fist. But on opening night, the Klan lurks around every corner—and so too does someone else, whose power is something darker. Unbeknownst to the Smokestack Twins, vampires are descending on Clarksdale, their glowing eyes set on Sammie’s otherworldly power.

When I added Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu to this list last year, I attributed its immediate #4 placement to Eggers’ laser focus on historical detail and innate understanding of Gothic horror. With the arrival of Sinners, we’re in a true vampire renaissance. Rarely do filmmakers operate with the intricacy—nor the historical reverence—of Eggers and Coogler. Where Eggers’s film was an homage to the 19th-century Gothic, Sinners is a collage of a thousand cultural moments, as much a history of the Blues (with nods to the legend of Robert Johnson and an all-too-perfect cameo from Buddy Guy) as it is to the cinematic vampire (the From Dusk till Dawn parallels are clear from the start, but Coogler also works in smaller visual homages to Coppola’s Dracula, Murnau’s Nosferatu, and more). Every shot is steeped in centuries of history, coming to a head with the (stunning, nearly indescribable) magical realist odyssey that is Sammie’s first musical performance, one that summons ancestors and imagines a future unknown to him and may literally burn down the walls that keep him in, if he lets it work its magic. He’s pierced the veil between the living and the dead, and what emerges is sometimes horrifying, but always glorious.

Then, by the same token, Sinners becomes the most horrifying vampire film in recent history. Coogler operates at a level beyond jump scares (though Sinners has a few) and gore (though there is much)—the horror in Sinners is dread. The Moore family begins the story pondering rotting in hell or inadvertently letting the Devil follow them home, and we end wondering if they’ve experienced just that. They take refuge in the Blues—the one thing that truly belongs to them—and upon hearing it, the Devil does follow them home, in the form of a white man (Jack O’Connell) standing at their door, demanding a chance to extract their power, bending their bodies and taking their souls when they refuse.

In a much-needed break from traditional horror structures, Coogler gives full weight to each of the deaths that make up Sinners’ (devastatingly high) body count. There is no accidental death, nor gunshot fired, nor vampiric turning left unfelt. In the morning, when the vampires are long gone, the fragments of a once-vibrant community will return to find their loved ones disappeared, vestiges of the Klan left in their place. Sinners was always horror, but never fantasy.

In Sinners, vampirism is colonial and all-consuming, reshaping each victim in the image of its white progenitor—but then again, so is life outside of it. As the vampires themselves are happy to reveal, supernatural monsters were hardly necessary to exact the Smokestack Twins’ fate, or the destruction of their community: with white hoods tucked under their beds, real-life monsters were already on the way to ensure that fate came to pass.

Freedom may have always been an elusive dream for the twins—for the entire Sinners ensemble. Every character’s fate may have been sealed long before they ever stepped foot in Club Juke. That doesn’t stop them from trying to escape it, nor the audience from hoping—praying—that somehow, against the odds, they do.

2. Carmilla, the novel by J. Sheridan Le Fanu, edited by Carmen Maria Machado (Lanternfish Press Clockwork Editions, 2019, originally published 1872)

A disclaimer: any ranking of Carmilla is an injustice. Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella was published a full 25 years before Stoker’s Dracula, and—unlike fellow predecessor “The Vampyre”—rivaled it in storytelling and prose, but never came close to the same recognition.

Carmilla is a coming-of-age story—born long before the canon embraced such a thread—about grief, taboo, and sexual repression from an era where such themes pulsed beneath every element of the literary and cultural world. Set in an isolated castle in the remote forests of Austria, Le Fanu places a young woman at the center of his horror story—Laura, a lonely teenager living with her grieving father when a carriage crash leaves a mysterious young woman in their care. Here lies Le Fanu’s monster: Carmilla, this undeniable other, a creature enigmatic in every sense except for her pulsing queer desire.

If Dracula lives on in virtually every vampire who came after, so too does Carmilla, if in subtler forms. In Interview with the Vampire’s grief-addled isolation, in Twilight’s hormone-heavy desire, in Hotel Transylvania’s overprotective single father, and in Humanist Vampire’s bildungsroman, she is ever-present, even if she remains invisible.

But even more striking: Carmilla experimented in ways that would take the genre centuries to catch up. Not until the era of Woman, Eating, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, and Thirst—i.e., not until recently—did the canon truly seem interested in exploring the intricacies of the female vampire, despite Le Fanu building the foundation 150 years earlier. Not until 2019, when Carmen Maria Machado revisited the novel for an annotated new edition, blending archival analysis and cultural criticism with new original fiction, did another writer come close to matching the original. Carmilla never quite achieved Dracula’s status as the seminal work of vampire literature.10 But, given the radio silence that came after its unabashedly bold experimentation, perhaps it should have.

1. Dracula, the novel by Bram Stoker (Penguin Classics, originally published 1897)

Ultimately, there’s a reason any ranking of Carmilla is an injustice: her younger brother cannot go ignored.

In the darkest reaches of Transylvania, a young, naive Englishman arrives at a remote castle to handle the business dealings for his new employer, the mysterious nobleman Count Dracula. Before he—or his reader—has quite processed what’s going on, he’s become a prisoner in the castle, and the enigmatic Count is descending upon London, leaving destruction in his wake. It is a story we cannot stop retelling.

Though it runs over 400 pages, Dracula never lulls. Instead, its insidious villain lurks in the background of every epistolary chapter, the full truth of his monstrosity never shown all at once. All the while, another layer of insidiousness builds underneath: the true bias behind his would-be victims’ anxieties. He was at once a pivotally distinctive character and a blank canvas for the human characters to project the most visceral of their fears, united in an Us-vs-Them dynamic against the ultimate other. It’s no wonder the character was so rapidly a target for recreation.

Dracula’s readers picked up on his potential quickly—in the years that followed, the count became the original movie monster with the release of Nosferatu, then further shaped the nascent film genre with Lugosi’s take. Then, he was everywhere: the ubiquitous vampire whose face itself (in the form of Lugosi-as-Dracula’s distinctive look) was synonymous with the genre Stoker built.

But Dracula is more than just its cultural impact: the most important vampire novel in the canon maintains its status at least in part because it’s also the best-written vampire novel in the canon. Dracula is a hedge maze of social anxieties, from immigration and cultural otherness to sexual desire and fluidity, to the fear of societal transformation itself; and that maze is supported by the novel’s format, an epistolary collection of fictional letters, diary entries, news reports, and legal documents from an array of characters so intricate that no one figure emerges as a solitary hero, even as the iconic monster stands alone—in his own novel in the canon. In all its complexity, Dracula consolidated—and often, established—the tropes that would come to define the genre. But far beyond the foundation it laid, Dracula was a masterwork all on its own.

The Rest (in order)

29. Vampire’s Kiss (1988, dir. Robert Bierman)

30. Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995, dir. Mel Brooks)

31. The Twilight Saga film sequels, New Moon through Breaking Dawn—Part 2 (2009-12, dir. Chris Weitz, David Slade, & Bill Condon)

32. Hotel Transylvania (2012, dir. Genndy Tartakovsky)

33. The Last Voyage of the Demeter (2023, dir. André Øvredal)

34. Hotel Transylvania 2 (2015, dir. Genndy Tartakovsky)

35. The final two seasons of HBO’s True Blood (HBO, 2013-2014)

36. Netflix’s Hemlock Grove (2013-2015)

37. Renfield (2023, dir. Chris McKay)

38. Dracula Untold (2014, dir. Gary Shore)

39. The Invitation (2022, dir. Jessica M. Thompson)

What’s Next?

My Watchlist (and Reading List)

Film & TV:

Abigail (2024, dir. Matt Betinnelli-Olpin & Tyler Gillett)

Blade (1998, dir. Stephen Norrington)

Salem’s Lot (2024, dir. Gary Dauberman)

Shadow of the Vampire (2001, dir. E. Elias Mehrige)

Books:

Fledgling by Octavia Butler (Seven Stories Press, 2005)

Lucy, Undying by Kiersten White (Random House Worlds, 2024)

Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas (Berkley, 2023)

Notable Omissions

Interview with the Vampire (the 1976 novel by Anne Rice) and Interview with the Vampire (the 1994 film)

What can I say? First, the book elicited in me a boredom so profound I could feel it in my soul. Second, regardless of how dedicated I was to my research for this list, I could not possibly spend that much time looking at Tom Cruise, much less Brad Pitt.

The Vampire Diaries (The CW, 2009-2017)

See the above note about Tom Cruise. It also applies to Ian Somerhalder.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (The WB, 1997-2003)

I am, admittedly, a Buffy virgin. With any other series, that might have been okay; but Buffy is so intricate—its most dedicated fans so dedicated—that anything less than utter devotion to the source material felt like an unsatisfactory place from which to approach the series. But I will get there one day, and I will return.

Thanks for tuning in to this special edition of “What I’m Reading,” a biweekly recommendation guide from Alienated Young Woman. If you’ve enjoyed this post, consider sharing it on your socials. Subscribers receive two free reading guides per month and one long-form review.

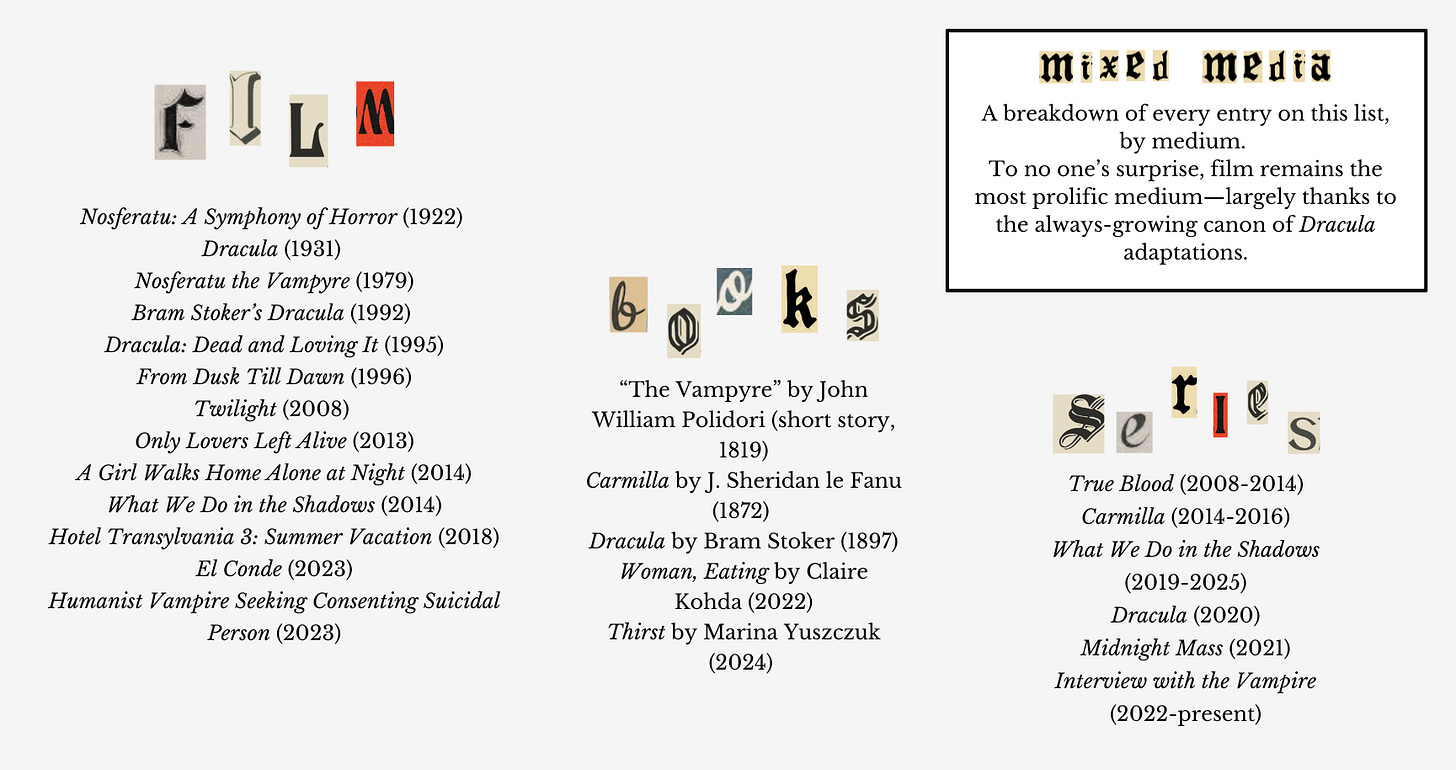

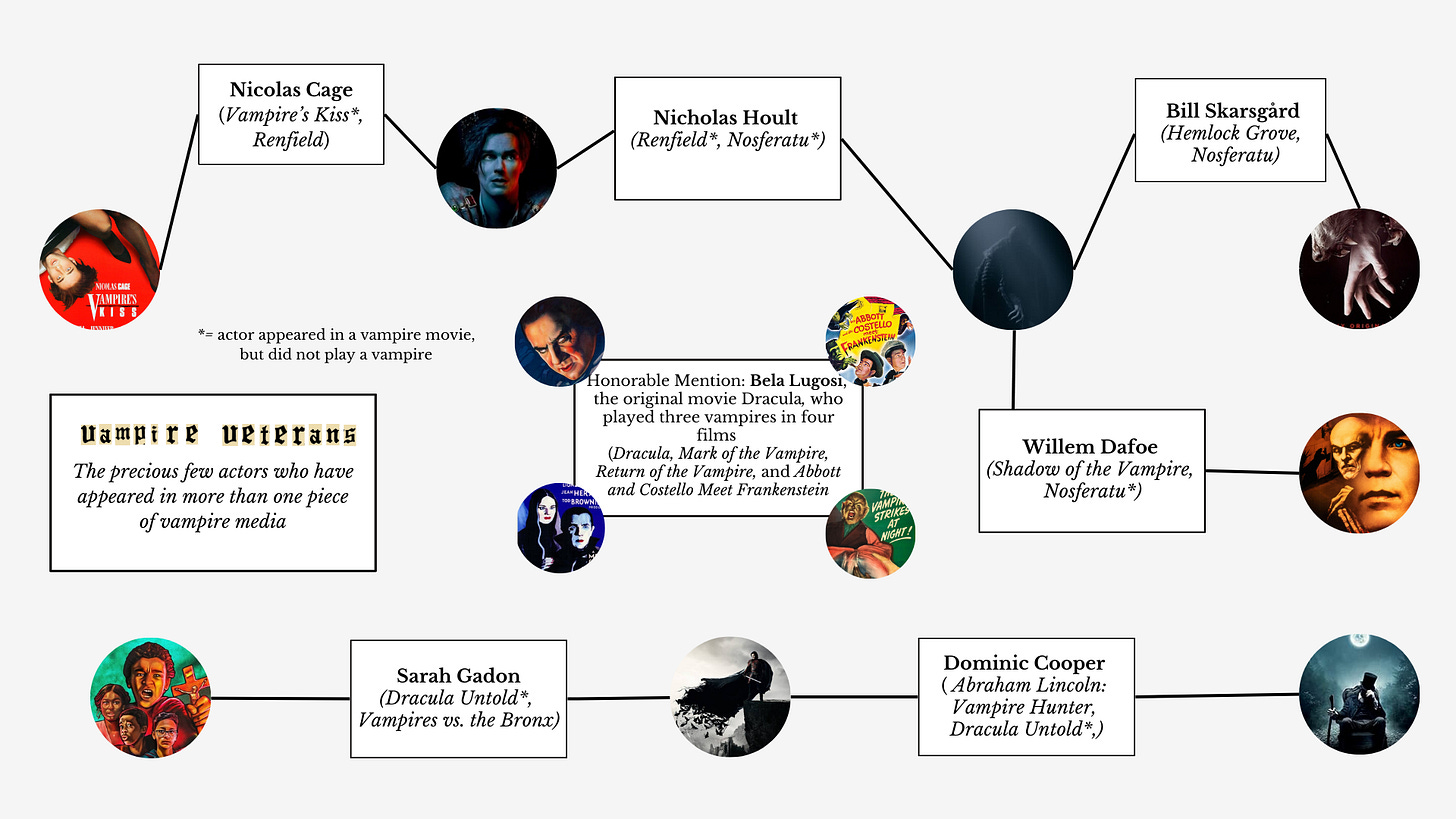

All visuals by the author.

An abridged ranking of Van Helsing portrayals:

Harvey Guillén as Guillermo de la Cruz (nee van Helsing) in What We Do in the Shadows (2019-2025)

Hugh Jackman as Gabriel “van Helsing” in Van Helsing (2004)

Anthony Hopkins as Abraham van Helsing in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Jim Gaffigan as the preserved head of Abraham van Helsing in Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation (2018)

Edward van Sloan as Abraham van Helsing in Dracula (1931).

Stay tuned for a full list of seminally hot vampires. I’ve been thinking on it a lot.

Obviously, AMC’s Interview with the Vampire—which premiered eight years after Carmilla—now takes the cake when it comes to embracing the queer themes of its source material. True Blood, a queer allegory from the outset and a predecessor to the YouTube series, became better about incorporating explicit queerness the longer it ran. Interestingly, we have yet to see a Dracula that leans fully into the novel’s queer undertones, though to its BBC’s otherwise misguided 2020 adaptation does, to its credit, consider this thread.

Chilean production, narrated in English with some Spanish and French dialogue (English captions).

The Haunting of Hill House is (very loosely) inspired by Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel of the same name. The work of Henry James inspires Bly Manor, especially the novella The Turn of the Screw and the short story “The Romance of Certain Old Clothes” (though each episode is named for a different story). In a similar manner, The Fall of the House of Usher takes its inspiration from Edgar Allen Poe’s 1839 short story of the same name, but each episode between the pilot and finale is also an adaptation of a different Poe story, including “The Masque of the Red Death” and “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

Iranian production, spoken in Farsi with English subtitles.

I am not counting Marina Yusczcuk's Thirst because it’s not marketed as a direct adaptation, though there's certainly an argument to be made for placing it in the “inspired by” category.

Who (spoiler alert), in one breath, dethrones every Skarsgård, Reid, Anderson, and even Hayek as the unequivocal hottest vampire in cinematic history.

A close, CLOSE second to Lawson (see #7).

Machado, alongside Mariana Enriquez, may be our truest modern icon of literary horror.

this has made it so clear I'm slacking in my vampire media consumption?! Twilight and the 1922 Nosferatu are the 2 of 25 I've seen/read/etc. also-- so impressed by the visuals in this newsletter!