What I Read in February

In short, another big month for bisexuality, lucid dreams, and murder.

Thanks for reading Alienated Young Woman! Subscribe for free to receive biweekly posts like this one in my newsletter, “What I’m Reading.”

It’s almost springtime in New York. Gabby Windey is a champion and a newlywed. Chappell Roan’s “The Giver” finally has a release date. The Queer Adult Vampire Renaissance rages on. It’s a queer, windy spring.

Last month’s reading log was (appropriately) apocalyptic. In this month’s haul, our narrators take a much different approach to grief. Their pursuits are (thankfully) funnier, even if no less bloody. Some of them even have time to fall in love! As with January’s Poor Deer, these narrators occasionally feel so hard that they inadvertently manifest the supernatural. (This time around, it’s ghosts, psychic visions, and, in one case, vampires.) But in the end, they’re perhaps slightly more equipped to persevere.

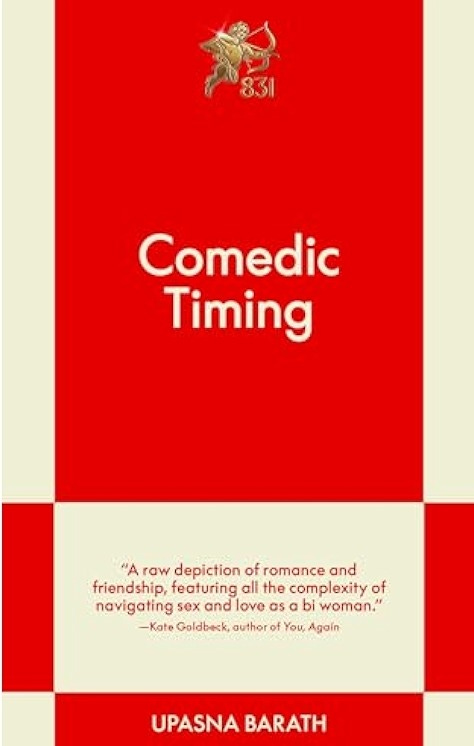

Comedic Timing by Upasna Barath (831 Stories, 2025)

I’m a well-documented observer of 831 Stories, and with its third novella, the imprint seems to be keeping up its streak of fresh, original stories. In playwright Upasna Barath’s literary debut, a bisexual woman feels ready for a new start after breaking up with her long-term girlfriend and moving to a new city. But when she catches herself falling for a man, that fresh start slowly becomes a full-blown identity crisis.

Barath’s writing feels almost like reading a diary (unsurprising given her background in personal essays) an effect that, when used sparingly, succeeds at giving the novella an organic, intimate sensibility. Structurally and thematically ambitious, Comedic Timing isn’t quite the well-oiled machine that was Big Fan. But it’s fun, sexy, and absorbing all the same, and Barath’s turn to literary fiction is undoubtedly exciting.

Hungerstone by Kat Dunn (Zando, 2025)

The Gothic sensation novel is back from the dead, and it’s in the most capable of hands. Set 10 years after J. Sheridan le Fanu’s original novel, Hungerstone reimagines Carmilla, trading in teen ingénue Laura for the steely 30-year-old Lenore, an English aristocrat whose robber baron husband keeps her similarly isolated.

Where novels like Marina Yuszczuk’s Thirst used Carmilla as a phantom framework, Hungerstone drops itself right in the center of Le Fanu’s world. The circumstances have changed, transporting us from the 1872 novel’s isolated Styrian wilderness to the heart of the English Industrial Revolution. For Lenore, it’s not just a supernatural creature looming in the shadows—human monsters lurk around every corner. The titular vampire, however, remains just as hypnotic, and perhaps even more mysterious.

With traces of The Woman in White and “The Yellow Wallpaper” in its blood, Kat Dunn reimagines a seminal vampire tale with a fiercely original vision that commands the same feral devotion as the original.

The Girls by John Bowen (McNally Editions, originally published 1986)

Had Shirley Jackson written We Have Always Lived in the Castle with the more satirical sensibility of her earlier work—and more importantly, had she finally dove head first into the queer undercurrents that ran through novels like The Haunting of Hill House and Hangsaman—she likely would have come out with something like John Bowen’s The Girls.

In the English country village where Bowen sets The Girls, mundanity feels just as ominous as in Jackson’s New England. His titular girls, Sue and Jan, don’t seem to mind. For almost a decade, the pair live a quiet existence as tchotchke shop owners, amateur farmers, and longtime lovers, until an identity crisis sends Sue fleeing to Greece for a month-long journey of self-discovery. When she returns to find Jan pregnant and the child’s father all too eager to be involved, the girls must test just how far they’re willing to go to protect their perfect, precarious life.

Playfully macabre and startlingly tender, The Girls is a one-of-a-kind love story that feels simultaneously ahead of its time and quaintly, distinctly of another era—or perhaps another world.

Family Lore by Elizabeth Acevedo (Ecco, 2022)

I’m interested in novels (like Melissa Lozada-Oliva’s Candelaria) that feel like the renaissance of the early 90s multigenerational Latina family saga, a la How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents and Dreaming in Cuban. Where Candelaria felt like a COVID-era response to those earlier novels, Family Lore feels more like a straightforward pastiche.

Told from the perspective of Ona, an anthropologist researching her Dominican-New Yorker family’s history, Family Lore follows two generations: Ona, her aunts Matilde, Pastora, and Camila, cousin Yadi, and clairvoyant mother Flor. The family has long since settled in Manhattan, but they’re thrown into chaos when Flor abruptly announces she’s hosting her own wake. New and long-buried tensions brew as Ona, Yadi, and the aunts attempt to find out what exactly Flor knows about the future—and what they don’t know about the past.

In its strongest moments, Family Lore is an homage to the 90s canon, as told by a protagonist who’s had the benefit of reading it. Though not quite as explicitly surreal as Candelaria, Acevedo’s novel is tinged with a magical realist sensibility. It’s the story of a family for whom magic lingers in every interaction, just beneath the surface.

Thanks for reading Alienated Young Woman! If you’ve enjoyed this post, consider sharing it on your socials. Subscribers receive 1-2 free reading guides per month.

Collage by the author.